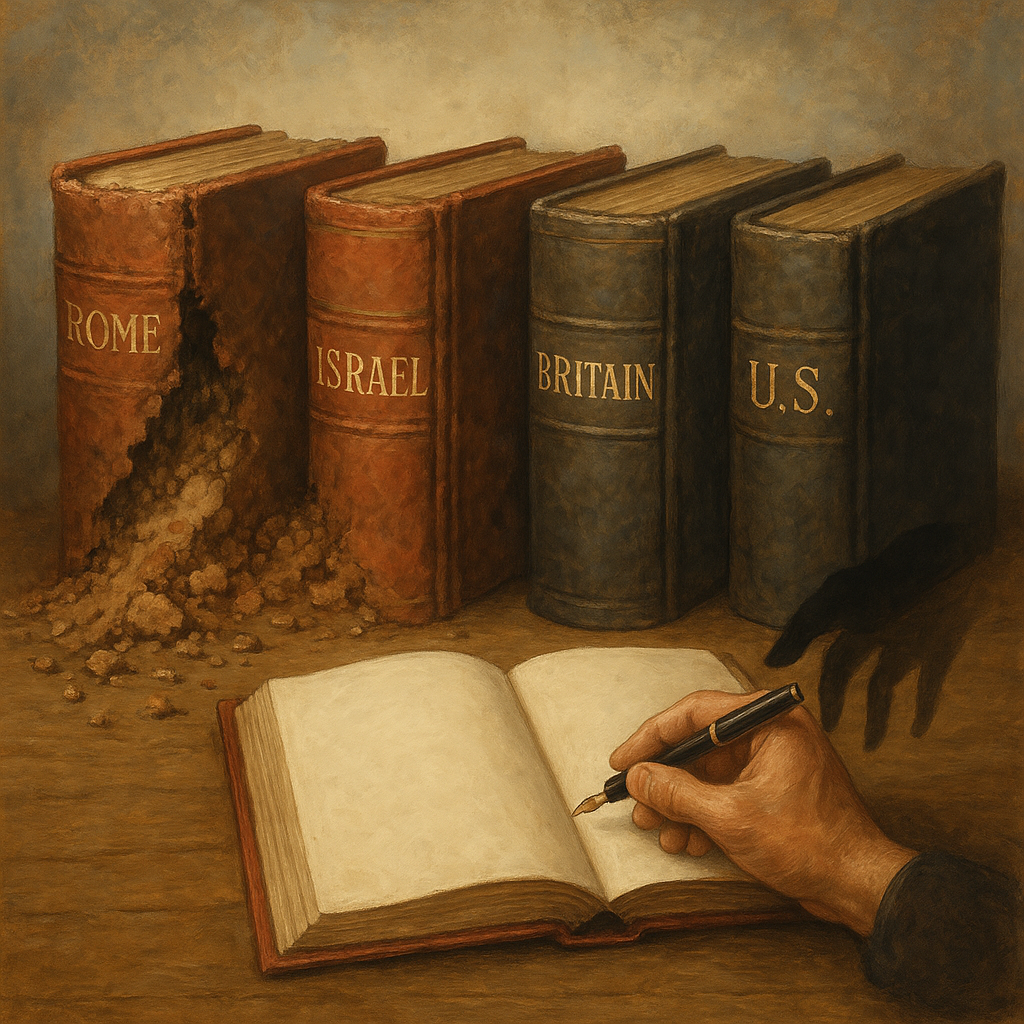

Will Durant once wrote that civilization lives in the clearing, and there’s always a hungrier tribe still in the bush, waiting to conquer it. Durant warned that no great civilization is ever conquered from without until it first destroys itself from within. The image is compelling, but the conclusion it supports is wrong.

Durant helped popularize the idea that civilizations follow a natural arc: birth, growth, decay, and death, but that’s not what history shows. Collapse is not the rule, but the exception. What defines most civilizations isn’t that they fall, but that they rise again. Time and again, people have remembered who they were, repented of who they became, and rebuilt what had started to crumble.

The only reason collapses stand out in our memory is because they’re final. The civilizations that recovered don’t mark an end, but only become the next chapter. When civilizations don’t recover, they are remembered only for how they ended, but when we look more closely most of them could have ended many times before they finally succumbed, and some lasted for thousands of years.

Let’s look at five cases: Israel, Rome, the Christian Church, the British Empire, and the United States. Each one faltered, each one was tested, and each one chose rebirth, often more than once. Then we’ll turn to the one system that breaks this cycle, an ideology that produces collapse, and never renewal.

Israel: Chosen, Rebellious, and Restored

Israel wasn’t founded on conquest or wealth, but on covenant. Its strength was moral before it was military. When it kept to its purpose, it thrived. When it strayed, toward idols, injustice, or pride, it declined. But it wasn’t a straight descent. Time after time, the people returned, and God restored them, not because they were perfect, but because they remembered.

Allow me to briefly dispel something that might be off-putting to some readers. I am a Christian, so I believe the people of Israel were restored because they returned to God, but a secular reader would read it not as a ‘return to God’ so much as a return to First Principles. With Israel (and later, Christianity), God is the First Principle, so the language is fitting, but the framework I’m drawing is not based on religion. This is an accurate reading of history.

During the period of the Judges, Israel cycled through at least seven major episodes of rebellion, decline, and deliverance. Othniel, Ehud, Deborah, Gideon, Jephthah, and Samson all responded to national failure. The people would fall under foreign rule, cry out, and be delivered in a way that wasn’t incidental, but was the rhythm of the nation.

Even under the monarchy, the cycle persisted. Saul failed, David repented, and Solomon drifted, leading to the division of the kingdom. The northern kingdom (Samaria) never returned to God and was conquered by Assyria in 722 BC, but the southern kingdom (Judah) saw several revivals, under Asa, Jehoshaphat, Hezekiah, and Josiah. Each led a brief return to righteousness, and each led to renewal.

Before both kingdoms fell, Israel had already experienced a dozen national restorations. It didn’t fall because it failed once, but because it finally stopped coming back.

And even then, the story didn’t end.

Judah was conquered by Babylon in 586 BC, but seventy years later, Cyrus the Great issued a decree and the Jews returned. The Temple was rebuilt, and the law was restored. Ezra and Nehemiah rebuilt not just walls, but national identity.

Later, under foreign rule, Israel rose again. The Hasmonean revolt led to the reestablishment of an independent Jewish state for about a century, and while Roman conquest ended that, the pattern continued. In 1948, after nearly two thousand years of dispersion, the Jewish people reestablished a nation.

Israel was not conquered once, but many times, and yet it kept coming back. It did not always come back in the same form. Sometimes it returned politically and sometimes spiritually, but it always eventually returned.

What failed was never the First Principles, but the will to uphold them, and each time that will returned, so too did the nation.

Rome: Two Thousand Years of Rebirth

From the founding of Rome in 753 BC to the fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD, Roman civilization endured for 2,206 years. It passed through monarchy, republic, empire, division, and relocation. Christianity replaced paganism, and though Rome was invaded, fractured, and corrupted, it endured until the Ottoman Turks finally took Constantinople, after the Great Plague had halved Byzantium’s population.

Had it not been for the Great Plague, Byzantine might still endure to this day.

We tend to think of the Roman Empire as having fallen in 476 AD, but the Byzantine Empire was not a successor state; it was Rome. Byzantine rulers bore Roman titles, Byzantine laws derived from Roman codes, and Byzantine citizens saw themselves as Romans.

People tend to forget that Rome did not split into two empires, but became so big that it had to be ruled from two separate locations to keep it intact, and though the Eastern Roman Empire governed from Constantinople, the empire never actually changed, enduring for nearly a thousand years more.

Only when the Ottomans breached Constantinople’s walls in 1453 did the Roman line finally break. And even then, the memory of Rome shaped the Renaissance, Enlightenment, and the modern West. There is, after all, a reason that the fall of Constantinople and the Renaissance occurred around the same time – those who could flee the Ottoman Turks did, and they brought with them what had been lost: Roman culture, art, and science – the very things whose absence had helped cause the Dark Ages.

Many believe the Renaissance began when Islamic scholars reintroduced classical knowledge to Europe, and while this is partially true, what Islam preserved and transmitted came from their conquest of Byzantine territories.

It’s not just that the Black Death disrupted the West. It hollowed out the Byzantine Empire, leaving it too weak to resist the Ottomans. When Constantinople fell, the heart of Rome returned. That infusion of classical knowledge into Italy was not an accident of trade or a revival of curiosity. It was a direct consequence of plague and conquest. The Black Death did not just help end the Dark Ages by destabilizing Europe; it ended the Dark Ages by bringing Rome back.

There is wisdom in this: even in the darkest of times, it was the Black Death that ended the Dark Ages.

The Byzantine Empire endured through at least five major cycles of decay and renewal. After the fall of the Western Empire, Byzantium reasserted Roman law and order under Justinian. When it nearly collapsed under Arab invasions in the 7th century, it rebounded through military and administrative reforms. The Macedonian dynasty led a cultural and territorial renaissance. Following a catastrophic defeat at Manzikert in 1071, the Komnenian emperors restored the empire again. Even after the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople in 1204, the Byzantines returned in 1261, reclaiming their capital and reviving the state again.

I started this section focusing on the Eastern half of the Roman Empire because it lasted so long, but the same pattern holds true for the Western half, which survived three major periods of collapse and recovery. In the 3rd century, amid civil war, economic ruin, foreign invasions, and breakaway states, the empire nearly disintegrated, but was pulled back from the brink by Aurelian, who reconquered lost territory, and Diocletian, who restructured its administration and military.

These were not small adjustments; each was a genuine recovery. After Theodosius’s death in 395, the Western Empire began a long decline it could have, but did not reverse. Rome would be sacked, North Africa lost, and imperial power gradually replaced by barbarian warlords. The empire didn’t fall because it never recovered. It fell because, after so many recoveries, it finally lost the strength to rise again.

Ironically, the Huns and Visigoths who sacked Rome did so not as foreign invaders in the traditional sense, but as Roman legions, mercenary forces who, due to rampant inflation and the devaluation of the denarius, could no longer support their families and turned on the empire that failed to pay them. The groups that finally destroyed the Western half of the empire were not trying to end Rome – they just wanted to be paid.

Even before Rome split into East and West, the Classical Roman period passed through at least five major cycles of decay and recovery, each threatening the system, and each answered, until the split, by reform.

After the death of Augustus, emperors like Caligula and Nero brought instability, but order was restored under Vespasian. Following the golden age of the Five Good Emperors, Commodus and a series of weak successors plunged the empire into chaos. The third century nearly destroyed Rome entirely through civil war, secessions, plagues, and invasions, yet it recovered again under Aurelian and Diocletian. After the Tetrarchy fractured, Constantine the Great reunified the empire, moved the capital to Constantinople, and restructured both church and state. Theodosius I would hold the empire together one final time, reasserting unity in both theology and law. When he died, the empire was permanently divided, but not before proving, over and over, that Rome did not endure because it avoided crisis. It endured because it refused to let crises become collapse.

The Church: Truth Endures Where Institutions Fail

The Christian Church began in humility and sacrifice. It had no armies and no borders, and yet it changed the world. With power came rot, and over time, bureaucracy replaced devotion.

In a grim inversion of the Eucharist, where bread becomes the Body of Christ, the Church, once also called the Body of Christ, became an empire. That empire even became literal in the form of the Papal States (territories in central Italy governed directly by the pope from the 8th century until 1870).

By the time of Gregory VII and Innocent III, spiritual leadership had become political command. The Church crowned emperors, excommunicated kings, and dictated terms to monarchs. The medieval Church levied taxes, launched crusades, and prosecuted heresy through inquisitions. In many places, it blurred the line between salvation and subjugation.

By the time of the Reformation, that decay was impossible to ignore. The sale of indulgences (monetized forgiveness) sparked outrage. The Church had built opulence on top of poverty, but the Reformation was not a rejection of Christ so much as a plea to remember Him.

Luther’s 95 Theses in 1517 were aimed at correcting doctrine, not destroying faith. The wars that followed, bloody and brutal though they may have been, weren’t really about Christ; They were about power.

Theology was the banner. Power was the motive. What the empire feared wasn’t heresy; it was the rebirth of actual Christian belief.

Once Catholicism gave up on crushing Protestantism, it had to compete with it. The Catholic Counter-Reformation began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563), which reasserted doctrine, reformed clerical abuses, and reinvigorated pastoral care. Orders like the Jesuits emerged not to silence Protestants, but to out-teach them. It was a quiet transformation, but no less real: a spiritual reawakening inside the very institution that had lost its way.

Now both Catholicism and many Protestant churches are in a period of decay as they chase a younger and more secular audience, replacing spiritual purity with modern sentimentalities. The Church Growth Movement and seeker-sensitive models, while well-intended, often sacrificed truth for appeal. Whether or not these institutions survive is not the issue as other churches are staying true to the Bible, and those churches are thriving.

Even now, the Gospel survives. The Church has been reborn not because of institutional strength, but because the truth it carries cannot be killed.

The British Empire: Decline Without Disappearance

Like every great power, Britain knew both failure and renewal. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 checked absolutism and reaffirmed Parliament’s supremacy, breathing new life into the ideals of the Magna Carta. Later, as the moral contradictions of empire became impossible to ignore, Britain didn’t collapse; it reformed. The abolition of the slave trade in 1807, followed by the abolition of slavery itself in 1833, was not the end of empire, but its moral rebirth, arguably marking the moral peak of the empire, and when Britain could no longer sustain global domination, it did something no empire had done before: it gave power back. The postwar transformation of empire into Commonwealth wasn’t collapse, but reinvention. Britain handed self-rule to its former colonies and turned command into cooperation. These were not acts of decay, but of conscience. The British Empire didn’t fall because it failed. It stepped back because it remembered what it was.

Unlike the sharp collapses and dramatic recoveries seen in Rome or Israel, Britain’s renewal came through conscience rather than catastrophe, with reform rather than revolt. When the cost of dominion became too high, Britain did what no empire had done before, handing power back, and reshaping its influence through the Commonwealth. Its declines were less dangerous, its revivals less dramatic, but the cycle is there all the same: a rise through power, a reawakening through principle, and now a decline through forgetting.

Christianity gave rise to the Magna Carta, the Enlightenment built on it, and the British Empire carried it across the globe. Most modern accounts of colonialism treat it as inherently evil, and in some cases, such as the Dutch East India model, that’s fair, but not all empires behaved the same. France extended full citizenship to its colonial subjects, and though Britain initially approached its colonies through exploitation, it gradually learned that the more prosperous its colonies became, the more prosperous England became. Mercantilism failed; free trade worked, and it was Britain’s slow but decisive shift from mercantilism to open trade that enabled it to rise, not just as a conqueror, but as a global economic power.

Two inconvenient facts are rarely acknowledged today. First: wherever the Union Jack went up, the ideals of the Magna Carta soon followed. Second: if we look at today’s wealthiest nations outside of Western Europe, the map still looks suspiciously like the old British Empire. There’s a reason for that. It wasn’t exploitation that built modern Canada, Australia, or Singapore, but legal inheritance, political reform, and the export of ideas rooted in Christian morality and classical reason.

The Enlightenment, incidentally, cannot be separated from Christianity. It emerged not in opposition to religion, but through the encounter between Judeo-Christian moral order and Greek rational philosophy, preserved in Byzantium and reintroduced to the West after the fall of Constantinople. That synthesis gave the West its structure, and it was from that structure that Britain built something truly unprecedented: an empire bound not just by force, but by law, conscience, and eventually, moral self-restraint, and this is what made the British Empire unique.

One of its colonies, outraged by taxation without representation, sent a letter to the King containing a line the world had never seen: “All men are created equal.” King George wasn’t impressed, but that line was not an invention so much as an echo, falling in line with what the Magna Carta first expressed: that no man, not even a king, stands above the law. That’s a sticky idea that just wouldn’t go away.

Prior to the Magna Carta, England had no First Principles. “God Save the King” is not a philosophy. But with the Magna Carta, the English-speaking world began to organize its laws and customs around liberty, equality before the law, and the moral limits of power. It was not the first time a ruler had been constrained by law (that distinction belongs to Hammurabi) but it was the first time a global empire was governed by a tradition that required the sovereign to bow to a set of principles higher than himself.

It is common today to condemn the British Empire in sweeping moral terms and to blame “the white man” for slavery, but the truth is far more complex. Slavery was a global institution. When Jefferson penned the phrase “all men are created equal,” slavery was a global norm, practiced on every continent. There were more white slaves in the Middle East than black slaves in the Americas, and more black slaves were sent to Islamic lands than to the New World. European powers purchased slaves from African slave traders, most often on the North and West coasts of Africa, who sold their own people into bondage.

If we take the Magna Carta as the moral foundation of the British Empire, then it was Britain’s eventual faithfulness to those First Principles that led it to do what no other empire in history had done: abolish slavery across its domain, and then use its military power to pressure others to do the same. The British Empire, more than any other force on Earth, is responsible for ending the global slave trade. That is not moral evasion, but historical fact.

So where does Britain fit into the civilizational arc?

It rose on conquest, reformed itself through conscience, and reached its peak not in expansion but in moral clarity, when it began to apply its own principles universally. It did not collapse. It handed the world to its own children.

Today, its decline is not one of exhaustion or defeat. It is a decline of memory. Modern Britain no longer celebrates its principles. It apologizes for them instead, and like every other civilization in this essay, its future will depend not on its guilt, but on whether it remembers the good it once carried, and chooses to carry it again.

Unless Britain returns to its First Principles, it will not endure. The same is true of Canada, and much of Western Europe. These are nations drifting not from exhaustion, but from amnesia.

America: The Choice to Rise, Every Time

The British Empire, in decline, handed the world to one of its children: the United States. As Britain stepped back, we stepped forward as the world’s police force.

England took the Enlightenment and adapted it to monarchy. America, uniquely, built a nation on it from the ground up.

If someone had told General Cornwallis during the American Revolution that within a hundred years the United States would not only surpass England’s economy, but that of all Europe combined, he would have laughed, yet it happened.

America’s history is not a straight line upward, but a series of reckonings. We had our moments of moral, political, and institutional failure, followed by conscious return to First Principles.

The contradiction of slavery gave way to civil war and the constitutional amendments that redefined liberty. The corruption of the Gilded Age yielded to progressive reforms that reasserted fairness and accountability. The Great Depression nearly broke the economy, but it led to a reinvestment in national cohesion. Jim Crow segregation collapsed under the weight of a civil rights movement that insisted America live up to its founding creed. Even after political scandal and economic malaise in the 1970s, the country found its footing again by recalling rather than replacing its purpose. Over and over, America has faltered, and over and over it has chosen to rise, not by rewriting what it was, but by remembering what America was meant to be.

We often get our birthday wrong. We declared independence as thirteen colonies on July 4, 1776, and were loosely united under the Articles of Confederation, but our true national birth came on March 4, 1789, when the Constitution took effect, transforming a loose alliance into a moral and political union.

America was never perfect, but it came closer to the ideal than any society before it. Its founding ideals were not compromised by their imperfection in practice. They were defined by the aspiration to practice them more fully. Just look at the preamble:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

People don’t talk like that. Only nations do.

The Constitution is both a grant of power and a restraint upon it. It defines what the federal government can do, and if we followed it faithfully, it would do nothing more. The Bill of Rights, in turn, defines what no government may do, even in pursuit of its proper goals. The two work together: authority on one hand, boundaries on the other.

The Constitution not only empowers the federal government, but also affirms that all other powers remain with the states and the people. By rejecting monarchy, America rejected aristocracy, thus refusing a caste system.

The exception, of course, was slavery, and it was a grave exception. In retrospect, the very compromises that made forming a nation possible may also lead to its downfall.

It’s worth remembering: all of America’s per capita economic growth came from free states. The Antebellum South experienced no per capita GDP growth at all. That wealth gap still lingers, not as a legacy of exploitation by the North, but of the South’s own delayed participation in the American experiment.

The fastest rise in living and working conditions for ordinary people in recorded history occurred in the United States between 1789 and 1913, even though the South contributed no per capita growth until 1889.

The American Republic was built with eyes wide open. Its founders studied Rome’s collapse and Britain’s excess. They combined Christian ethics, Enlightenment ideals, and hard-won colonial experience into something new.

America was never perfect, but it was principled, and when it strayed it corrected. After slavery we fought for civil rights, and after depression, recovery. After scandal, we found reform, and after being attacked, we found resolve.

But today, that pattern is faltering. America is forgetting that rights come from God, not government. We forget that liberty requires virtue and that history matters, not for narrative, but for truth.

America is in crisis, but it is not economic.

It is spiritual.

Even now, rebirth remains possible, but like before, renewal has to be chosen.

The Exception That Breaks the Rule: Communism

There is one ideology that breaks the cycle. It does not lead to greatness, decline, and rebirth. It leads not to renewal, but to ruin.

That ideology is communism.

The economic pessimism underlying communism owes more to Thomas Malthus than to Karl Marx.

Thomas Malthus was born in England and became the world’s first full-time economist. His seminal work, An Essay on the Principle of Population, argued that population growth would always outpace food supply, leading to inevitable cycles of famine, disease, and decline, unless checked by moral restraint or catastrophe.

Ironically, this was written at about the same time Adam Smith noticed that in both England and the United States, food supplies were outpacing population growth, and by a wide margin. Adam Smith wrote, A Treatise on the Wealth of Nations, to examine what was different in England and the United States that allowed them to break out of the Malthian rut.

That Marx ignored Smith’s optimism in favor of Malthusian scarcity may be one of history’s most consequential misjudgments, as Marx, trained as a philosopher rather than an economist, made the faulty assumption that he could change all of the rules and incentives and production would not suffer. Marx offered a radical solution to a problem that free markets were already in the process of solving.

The problem, of course, is that there is nothing to share unless something is produced, and under communism, the incentives that drive production disappear.

Every society that has adopted communism has seen this collapse: the Soviet Union, Maoist China, North Korea, Cambodia, Cuba, Venezuela. Every single one. There is no reform in communism, as communism is the reform. There are no renewals in communism, as communism is the renewal.

The only thing communism has reliably produced is ruin.

Some will say that actual communism has never been tried, and that is true. Actual communism is not possible, which is why every attempt stalls in the dictatorship of the proletariat and goes no further.

Yet communism persists, not because it works, but because it adapts to infiltrate other nations, even as it fails. It behaves as a virus, killing its host as it spreads.

Cultural Marxism: Subversion by Design

When Marxist revolution failed in the West after World War I, theorists pivoted. The working class didn’t revolt and in fact, it became prosperous and patriotic.

The war had been the perfect breeding ground for communist thought as it represented war at an industrial scale. The officers came from the royalty and the enlisted men were commoners, a narrative framework that cast elites as villains and war as their instrument. The masses were supposed to revolt against the whole system, uniting into a brilliant Marxist utopia under the phrase, “Never Again!”

According to Marx, only countries that had already gone through the industrial revolution should become communist. Ironically, the first successful communist revolution occurred in Russia, a nation Marx himself believed was not yet economically ripe.

The Frankfurt School analyzed this failure and concluded that Western wealth and culture had to be dismantled, shifting their focus from the factory to the classroom.

Economic Marxism became Cultural Marxism. Oppressor and oppressed were redefined not by wealth, but by identity: race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, ability, even body type. The goal was not liberation. It was fragmentation.

Critical Theory emerged, and from it, Critical Race Theory. Critically, both in name and design, the ‘theory’ is not that oppression is the driving force of man, but that if you can fracture a society into identity groups and turn them all against the whole, that society will rip itself apart.

The real enemy wasn’t capitalism but Western culture, the Christian ethic, the nuclear family, patriotism, faith, and stability. All had to go, and when the working class refused to cooperate, it became the target. Their prosperity had to be reversed for the narrative to succeed.

This is why fossil fuels remain a target, even when carbon emissions can be sequestered. It’s not about the environment; it’s about control.

Saul Alinsky and the Bureaucratized Revolution

Saul Alinsky wrote the tactical guide. In Rules for Radicals, he advocated not open revolt, but strategic infiltration, using the system to destroy itself while exploiting its language to turn the systems strengths into weaknesses.

Alinsky’s most famous disciple was Hillary Clinton, who wrote her senior thesis on how Alinsky’s tactics would work better from inside the government.

Hillary Clinton never became president, but Barack Obama advanced the same strategy with remarkable effectiveness, bringing the United States to where it is today. Other world leaders have used the same strategy in other nations as well, from Merkel in Germany, to Trudeau, and now Carney (Canada’s new Prime Minister), in Canada.

Today, every major Western institution, from universities, to media, and even to corporations, has adopted the vocabulary of grievance and the machinery of control. Bureaucracies preach equity and schools push ideology, while corporations enforce conformity.

What began as revolution from below has become subversion from above.

We Still Have a Choice

I listed five civilizations, and some may argue that my call to return to First Principles fails to define what those principles are, but the truth is, every civilization is founded on something. We can debate which sets of First Principles are best, but the pattern remains: growth and renewal come from remembering them; collapse follows when they are forgotten.

Some may note that I spoke of colonialism in a positive tone, which is no longer the cultural norm, but I also spoke of it in a very negative light. History is neither simple nor clean, and there is room, especially in the case of the British Empire, to view it through both lenses. It was both.

Every civilization before us faltered, but most recovered more often than they collapsed.

Israel rose through repentance, Rome endured through reform, the Church survived through truth, Britain adapted, and America, so far at least, has always chosen to rise again.

But communism offers no return.

There is still a hungrier tribe in the bush, but now it wears a bureaucrat’s badge. War paint has been replaced by credentials. The hungrier tribe no longer burns books; it rewrites them instead, and if we forget who we are for too long, we will not rise again.

Collapse, however, is not the rule. Collapse is only what happens when we forget to renew.

Renewal begins with a new national commitment to First Principles.

There is an old saying: “Those who fail to learn history are doomed to repeat it,” but more often, those who do learn from history are doomed to repeat it as well because of those who don’t.

The choice before us is not mine to make alone. It is a choice we must make together.

We are at a fork in the road, and I urge us to take the one less travelled by.

The well traveled path leads to a Chinese-style totalitarian state, perhaps as a vassal to China itself, where technology is not a tool of freedom, but a leash of control, and every aspect of life is subject to the will of those in power.

The other path leads back to a more perfect union, one built not by reinventing America, but by completing it. We complete our more perfect union not by tearing down our First Principles, but by finally applying them to everyone.

Not in grievance.

Not in guilt.

But in liberty.